“Today, tomorrow, next week, the week after, privileged Wall Street insiders who are considering breaking the law will have to ask themselves one important question: Is law enforcement listening?”

– Preet Bharara, U.S. Attorney for Southern District of New York

When the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act (the “Act”) was passed in 1968, proponents lauded the Act as a new weapon against organized crime and its growing involvement in the importation and distribution of narcotics. For the first time, federal law enforcement was permitted to wiretap conversations of criminals with suspected involvement in a variety of serious offenses, including organized crime, gang-related activities, and drug trafficking. These techniques would prove to be a valuable addition to authorities’ arsenal in fighting blue-collar crime.

Fast-forward forty-five years later. Where once reserved for violent and narco-related crime, the use of wiretaps has evolved to become a potent tool in the fledgling battle against white-collar crime. This article examines the history of wiretaps, their foray into white-collar crime prosecutions, and a potentially cloudy future.

Wiretaps: A History and Expansion

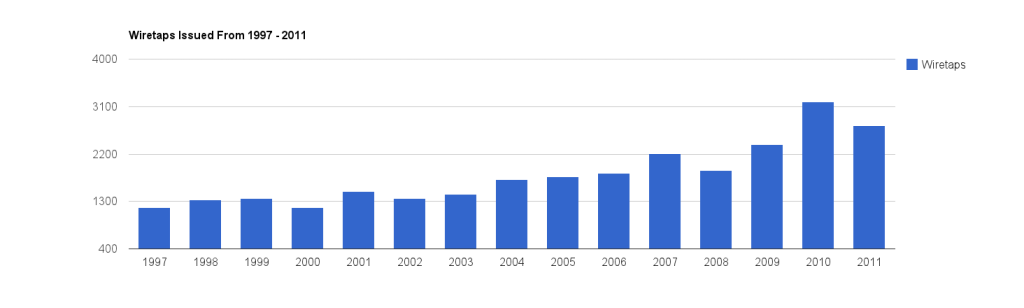

The use of wiretaps proliferated from the 1990s to the 2000s, with the amount of court-issued wiretap warrants surging from 1,190 in 2000 to 3,194 in 2010 – a nearly 200% increase. Their use, however, remained predominantly isolated to combating violent and drug-related crimes, owing partly to the strict process required for a judge to sign off. Indeed, many involved in passage of the bill recognized the fine line that existed between an individual’s privacy rights and authorities’ investigatory needs. The crafters recognized that any wiretap must be “conducted in such a way as to minimize the interception of communications not otherwise subject to interception,” with a focus on preventing unnecessary intrusion into the target’s privacy.

Wiretaps were intended to be a last resort, rather than a first choice, with Congress requiring that the government provide a “full and complete statement as to whether or not other investigative procedures have been tried and failed or why they reasonably appear to be unlikely to succeed if tried or to be too dangerous.” The consequences of failing to heeding this admonition were severe – evidence resulting from an improperly obtained wiretap could be prohibited from use at trial. For organized crime and drug-trafficking cases, this standard was often easily overcome or satisfied, as there existed few alternatives in building a case that did not present a real risk of danger to both authorities and the public.

When compared to the perils faced in a drug or gang-related investigation, however, the ability to satisfy the conditions for obtaining a wiretap are not as clear cut. For example, the possibility of satisfying the “too dangerous” prerequisite is drastically reduced, since while violent acts are not entirely absent from white-collar crime, their prevalence is the exception rather than the norm. Thus, a showing would likely be required that other investigative procedures have been tried and failed. In white-collar crime investigations, criminal prosecutions are often aided by a parallel civil investigation that has the ability to utilize a variety of fact-finding techniques. Thus, rushing to obtain a wiretap before exhausting or at least exploring these avenues could potentially result in a later motion to suppress. Additionally, there is the chance that the subject could learn of authorities’ suspicions, since while these investigations are usually not made public, a subject’s acquaintance could receive a subpoena or even the subject himself could be requested to submit sworn testimony themselves.

When the Act was passed, electronic surveillance was authorized only during the investigation of a list of enumerated offenses. This list did not include white collar crimes, and was initially limited to crimes pertaining to organized crime and narcotics. However, the list was expanded over time, eventually including crimes such as mail fraud, wire fraud, money laundering, bank fraud, and obstruction of justice in later amendments. Indeed, in early 2011, the Obama administration even proposed that wiretaps be authorized for prosecutions of criminal copyright and trademark offenses. Prosecutors also have the ability, as a result of Section 2517, to use properly obtained wiretap evidence to prosecute crimes that were not specifically listed in the Act. These revisions thus seemed to slowly lay the path for what would be an inevitable showdown with white-collar crime.